The second update from the three-part series on the oil spill is coming soon. There were some developments over the weekend we are hoping to include in that post - in the meantime, enjoy this "lighter" post on a much happier story:

Bar-tailed Godwit

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Every now and then you read something that truly inspires you. That was the case for me when I stumbled upon a story a week or so ago in the New York Times about a particularly long-flighted migrant, the Bar-tailed Godwit.

The Bar-tailed Godwit, a shore bird that breeds during summer on the shores of Alaska, crosses the Pacific annually to spend winters in the New Zealand/Australia region. It was long believed that because godwits don't have the ability to stop to rest and feed over the open ocean (like terns and other sea birds), they must have been stopping somwhere on land along their migration. They had been seen on the coasts of places like China and Japan during the spring, so many believed they just followed the Asian coastline down to Australia and New Zealand during the fall, stopping to rest and feed along the way.

One biologist, Robert E. Gill Jr., thought otherwise. As mentioned in the article, he studied birds before taking off for migration on Alaskan shores back in the early 1976. He was perplexed by how much the Bar-tailed Godwit fattened up before migration, even referring to them at one point as 'flying softballs'.

His hypothesis was that they actually flew much longer straight flights than scientists believed at the time. But lacking the ability to follow or track the birds' movement (there aren't many bird counts in the middle of the Pacific), it was left at that: a hypothesis.

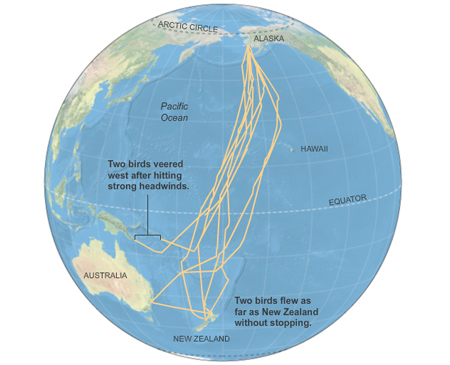

It wasn't until the 2000s that technology finally caught up with all these wild predictions. After installing the newer, smaller GPS trackers on migratory birds, scientists were able to finally see exactly when and where birds go during migration. In 2006 Robert was able to install the trackers in several godwits and track their migration.

Migration of several Bar-tailed Godwits from GPS

Credit: New York Times

Much to his excitement, it turned out his prediction had been right all along. Rather than skipping down the coastline with frequent stops, the Bar-tailed Godwits flew straight over the Pacific all the way to their wintering grounds. It took them a staggering 7,100 miles over 9 days in the air to reach their destination, which became a new world record for single longest flight. They then typically flew straight to spring stopovers in China, Korea, and Japan before returning to Alaska.

I've flown non-stop one time from Los Angeles to New Zealand, and I can tell you that even with the comfort of seats, complimentary drinks, and movies, it still wore me out pretty well. The will power of these birds to stay in the air for 9 straight days is something truly remarkable.

The New York Times also has a cool interactive feature including maps for several other long-distant migrants:

Interactive feature >

While I knew before reading the article that the Bar-tailed Godwit had been the longest recorded non-stop flight, the story itself of the evolution of GPS tracking and pre-GPS predictions (some of which ended up true) was the part that grabbed me. It was also incredible to read about how Robert had all along predicted this type of migration despite the general consensus thinking otherwise. GPS trackers are now being fitted on a variety of migratory species, and each year it seems they are getting smaller and more suitable to even smaller birds. The information recieved by these devices really helps us understand bird migration, but perhaps more importantly, how and where we can extend our efforts to protect them!

-David