Some troubling news came from the Northwest Territories a few weeks ago.

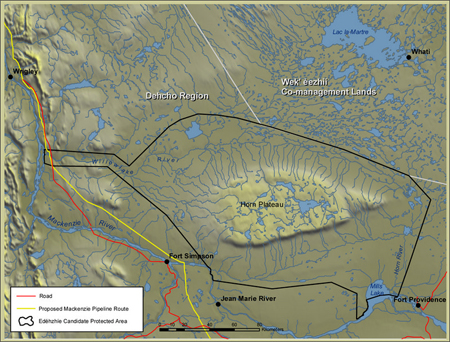

Edéhzhíe, an intact 14,250 square kilometer ecological gem in the Northwest Territories, ten years ago was placed under interim protection with the goal of eventually making it a National Wildlife Area. Also referred to as “Horn Plateau” this region features a unique teardrop shaped plateau that rises above the vast network of rivers and wetlands that surround it. It is home to woodland caribou, which have experienced extreme population declines, as well as nearly two hundred bird species. It is also a place of great cultural importance for the Dehcho and Tlicho peoples, who have used it for spiritual and everyday livelihood for centuries.

Map of Edéhzhíe and surrounding area.

Credit: Northwest Territories Protected Areas Strategy

Despite plans to make it a National Wildlife Area, the federal government recently indicated that while the surface land would be protected under such designation, sub-surface minerals are to be excluded from protection.

This essentially opens Edéhzhíe up for mineral exploration and mining despite those practices being banned in the region over the last ten years. Its original interim protection status, which included both surface and sub-surface protection, expired this fall. While the government is renewing its interim status, it has so far left sub-surface protections out of its renewal.

This is devastating news and it comes against strong opposition from the Dehcho First Nation, who argue that the decision is illegal and goes against their constitutional rights over the land. In addition, it goes against the recommendations of the final report authored by the Edéhzhíe Candidate Protected Area Working Group, a diverse group of local stakeholders brought together to provide a uniform vision for the future of the region.

Dehcho Grand Chief Gargan reiterated their strong opposition to the decision and made it clear they will do everything possible to reverse this decision:

“Canada’s decision is illegal and threatens this important habitat for woodland caribou, leaving the whole area vulnerable to exploration and mining. We won’t allow any staking to occur. Anyone who tries to stake in Edehzhie may have his stakes removed, and will be seeing us in court. Our constitutional land rights have been abused long enough by the way Canada applies the Canada Mining Regulations.”

Not only does it undermine the recommendations of the report – as well as Dehcho and Tlicho treaty rights – it undermines the entire purpose of creating a National Wildlife Area. How could one realistically set aside an area of land to protect wildlife while simultaneously allowing mineral staking and mining? It just doesn’t make sense...

Woodland caribou, in steep decline, are found throughout Edéhzhíe.

Credit: Valerie Courtois, Canadian Boreal Initiative

The stakes are high for wildlife. The region is home to three mammals—woodland caribou, wood bison, and wolverine-- that fall under Canada’s ‘species at risk’ designation (similar to endangered species in the United States). One of them, the woodland caribou, has been nearly been entirely extirpated from its original southernmost range. Now largely confined to northern boreal regions of Canada, including Edéhzhíe, it is extremely sensitive to industrial disturbance (mining being no exception), and it usually disappears from regions with extensive industrial footprints within decades, if not sooner.

Recent ecological assessments of Edéhzhíe have found as many as 24 fish species as well as numerous amphibian species, including the boreal chorus frog and wood frog. The abundance of surface freshwater throughout the networks of wetlands, lakes, and rivers provides optimal conditions for a host of water-dependent species

But these species could see their pristine waterways contaminated in years to come – many mining projects end up with excess pollution and waste byproducts with nowhere to go. They often leak into nearby drainages, and in more severe cases have been intentionally dumped in or near waterways as a way to cut costs.

Waste and contaminated liquids from mines often end up in waterways.

Credit: Garth Lenz

The area is especially important for many migratory birds as it’s located in the heart of the Mackenzie Basin, one of the largest migratory bird flyways in North America. It is also home to numerous lakes that are well-used by waterfowl and shorebirds, including Mills Lake, a Canadian Important Bird Area that attracts thousands of migratory waterfowl every year during migration.

Waterfowl were prominent throughout the region with a total of 28 species found, the six most common being Lesser Scaup, Surf Scoter, Canada Goose, Mallard, American Wigeon and Common Goldeneye. Shorebirds, including Semipalmated Plover, Least Sandpipers, and Lesser Yellowlegs, were among many that use the wetlands of Edéhzhíe. Bonaparte’s Gulls are also common breeders.

Lesser Yellowlegs are one of numerous shorebirds in the region.

Credit: Glen Tepke

On the raptor front, the Short-eared Owl and Peregrine Falcon, which occur in Edéhzhíe, are listed by the Canadian government as of ‘special concern’. A wide variety of songbirds nest within the forests and peatlands of Edéhzhíe including Swainson’s Thrush, Palm Warbler, Blackpoll Warbler, White-crowned Sparrow, American Tree Sparrow, and White-throated Sparrow

Overall, the region stands to gain little through allowing mining to be excluded from its protection. The government cited the exclusion as a way to provide a better ‘balance’ between the environment and economy. However, the Aboriginal communities who live closest and would be most affected have overwhelmingly expressed opposition to allowing mining, and the report by the Edéhzhíe Canadate Protected Area Working Group, which was designed to provide objective and balanced recommendations for the region, also did not include allowing mining in its recommendations.

One of the many rivers that flow through Edéhzhíe.

Credit: Northwest Territories Protected Areas Strategy

Worse yet, it sets a dangerous precedent in a region with numerous interim protected areas. Should mining be allowed in a place labeled as a National Wildlife Area, what will this mean for other regions undergoing similar planning processes?

The costs are simply too high for wildlife – while the region currently enjoys an abundance of life and species diversity, this could change if mining exploration were allowed throughout Edéhzhíe. Many of the species observed in Edéhzhíe have already seen their habitat further south destroyed by expanding industry, and now this threat is being pushed into the heart of their intact safe havens further north.

It’s time we take a step back and think about the bigger picture, for once.

The Edmonton Journal ran a story last week about this issue and the opposition from local Aboriginal groups. Read the story here:

Read Edmonton Journal article >