A few weeks ago I had the honor of being part of a tour of the proposed Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Site. There is no doubt that the region and the people there are incredible and I will write more about the trip in an upcoming blog entry. In the meantime I wanted to share this amazing good news about a core part of Pimachiowin Aki.

A small river within the Poplar River area

Credit: Garth Lenz

A vast stretch of pristine boreal forest and shoreline adjacent to Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba—a place where indigenous peoples, now members of the Poplar River First Nation (PRFN), have thrived for millennia—was finally placed under formal protection after years of hard, behind-the-scenes work between PRFN and the Government of Manitoba.

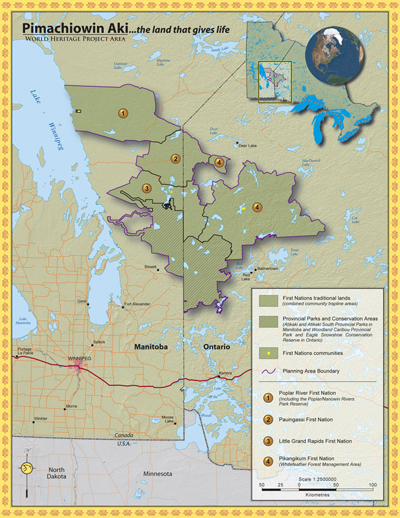

The traditional territory of PRFN, around the size of Yellowstone National Park, lies deep in the heart of Canada’s boreal forest and is a part of the single largest intact block of forest on Earth (which extends north and east of their territory). It also makes up a sizable portion of the hopeful Pimachiowin Aki UNESCO World Heritage Site, a proposed future Site which would protect much of this region under both natural and cultural designation due to the still-flourishing presence of indigenous communities. The formal protection of PRFN’s lands should prove to be a boost to the overall UNESCO designation effort, as it should ensure the ecological and cultural integrity of the region remain strong for years to come.

Map of the proposed World Heritage Site (Poplar is #1 on map)

Credit: Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Project

Every fall an annual moose hunt is held. This hunt is not just for maintaining a longstanding tradition; moose provide large quantities of food for this remote community and boost food stocks for the colder winter. Fur trapping, fishing, and other forms of hunting (such as waterfowl) are still integral to their way of life, and they identified as many as 50 different trees, shrubs, herbs, grasses, mosses and lichens as being used for their sustenance and spiritual livelihood. The PRFN made it clear that these types of traditional, sustainable forms of sustenance are far more desirable to them than short-term, invasive types of development seen in other parts of the boreal.

Willard Bitton navigates to his fall moose hunting grounds

Credit: Garth Lenz

This land use plan will prove vital for wildlife. Not only is it made up of important summer breeding habitat for birds--including Bay-breasted Warbler, Olive-sided Flycatcher and Rusty Blackbird--it also provides a safety net for the woodland caribou, an increasingly threatened species that has seen devastating drops in population and range as a result of sprawling industrial development. Perhaps most encouraging, however, is the nature of how the land use plan was created. The discussions and planning leading up to the announcement were led by PRFN and negotiated with the Manitoba government based on a government-to-government relationship. Too often are the territorial and treaty rights of local First Nations ignored in the decisions that affect their land; this showed that First Nation-led land use planning can be highly successful (and more importantly, ethical) and should serve as a model for future land use planning elsewhere in the boreal forest.

Olive-sided Flycatcher

Credit: Jeff Nadler

So a tip of the hat and a round of applause for the forward-thinking members of PRFN, Manitoba government, and the countless organizations and individuals who helped make this long-anticipated dream a reality!