With the advent of satellite transmitters (tags) small enough to fit on birds (large birds at least), our eyes have been opened to the dazzling migration feats that birds perform every day. We have chronicled a number of these feats here in this blog over the years including stories about scoters and eiders and godwits and Whimbrels.

Bar-tailed Godwit tracked via satellite tag:

/blog/?p=497

A Not-So-Common Eider:

/blog/?p=436

Hope the Whimbrel Spotted on St. Croix:

/blog/?p=177

Tracking Hope the Whimbrel:

/blog/?p=176

Scoters By Satellite:

/blog/?p=22

Whimbrels are one of my favorite birds—how can you not be enamored of a large shorebird with a large sickle-shaped bill and a name like “Whimbrel?” It is also a species of conservation concern that I profiled in my book Birder’s Conservation Handbook (click here to read the account).

The species has a fascinating distribution with both Old and New World forms considered by some to be separate species (the ones on the other side of the Atlantic have a white rump). In North America, Whimbrels have two distinct and widely separated breeding areas. One includes much of interior and north-coastal Alaska extending east to the Mackenzie Delta of the Northwest Territories. The other breeding areas is within the Hudson Bay lowlands from Nunavut south to Ontario. An estimated 76% of the North American breeding range is within the Boreal Forest ecoregion.

Starting in late July and August, Whimbrels begin moving south, stopping off in good feeding spots in southern Canada and the U.S. While small numbers winter in the southern U.S., the bulk of the population continues further south with large concentrations in South America.

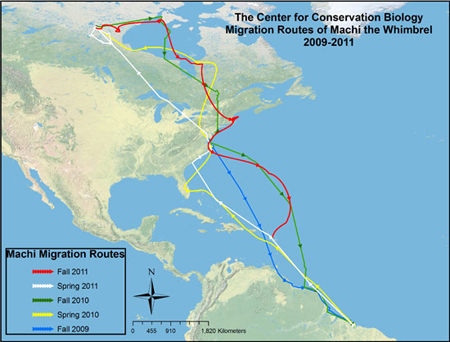

A few years ago, the Center for Conservation Biology headed up a new project to find out more about the movements of Whimbrels by putting satellite tags on some that used stop-over sites in Georgia. People from all over the world were amazed to follow tagged birds like “Winnie” who flew a non-stop nearly 5,000 mile flight to the Mackenzie Delta and “Hope” who nested in the Mackenzie Delta and later was tracked to St. Croix on her return. We all held our breath this past August when “Chinquapin” flew into Hurricane Irene but somehow made it through and arrived safely in the Bahamas.

That’s why it was such a crushing blow to many when two of the satellite tagged birds—“Machi” and “Goshen”—made their way back from nesting grounds in Nunavut and northern Ontario and amazingly beat through hurricanes and tropical storms to make landfall on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe in September where they were shot and killed at a hunting swamp soon after arrival.

See press releases from Center for Conservation Biology:

http://ccb-wm.org/news/news_pressreleases.cfm

Migration route of Machi, ending at Guadaloupe in red

Credit: Center for Conservation Biology

Not surprisingly there has been much discussion about these birds and the question of whether Whimbrels and other shorebird species should be hunted. Until the early 1900’s, shorebird hunting of all kinds was a common practice throughout North America. Where I am from in Maine, Eskimo Curlews (a smaller but close relative to the Whimbrel) were sometimes hunted in the fall and shipped to Boston restaurants before they became extinct. Except for American Woodcock and Wilson’s Snipe, it is now illegal to hunt shorebirds in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico and in many other countries.

Recreational hunting for shorebirds is still practiced in many parts of the Caribbean but on some islands there has been increased awareness by shorebird hunters of the conservation needs and implications for shorebirds. Hopefully the spotlight on these issues that resulted from the loss of “Machi” and “Goshen” can be focused towards positive changes for conservation.

Read more about this incident and shorebird hunting in the Caribbean at:

http://www.birdlife.org/community/2011/09/shooting-of-whimbrels-sparks-calls-for-regulation-of-shorebird-hunting-in-the-caribbean/

And the American Birding Association’s response at:

http://blog.aba.org/2011/09/abas-ned-brinkley-makes-birders-voices-heard-en-francais.html

And from Society for the Conservation and Study of Caribbean Birds:

http://www.scscb.org/