Draped across the shoulders of North America lies a forest so vast, pristine, and filled with birdsong that one would be forgiven for thinking they’d lept into the pages of a fairy tale upon visiting it for the first time.

Each spring, billions of migratory birds across the Western Hemisphere flock to this northern gem to nest and raise their young over the warm summer months, transforming each morning into a dawn chorus.

Do you know what forest I’m referring to?

If you reside in the north or read up a lot on birds, you likely do. But many Americans, and even some Canadians, are less familiar with the Boreal Forest despite the fact that it spans the width of North America—from Alaska in the west to Newfoundland in the east—and rivals the Amazon in size and ecological importance. And unlike the Amazon, it’s in our own backyard.

From Canada down to the southern tip of South America, birds large and small set their eyes on the bugs and berries that blossom throughout the Boreal during spring and summer. Long-distant migrants like the Whimbrel congregate along the shores where the Boreal meets the Arctic Ocean to feast on the abundance of insects and crustaceans after trekking their way from South America. Dark-eyed Juncos—a common sight at U.S and Canadian birdfeeders in the fall, winter, and early spring—opt to ditch the convenience of feeders in favor of the fresh caterpillars, beetles, and other bugs that emerge further north once the forest has shed its snowpack.

While each bird comes with its own epic tale of migration, it is the number of bird species and sheer volume of individual birds that has led many to refer to the Boreal Forest as “North America’s bird nursery.”

Up to an astonishing 5 billion birds in total can be found in the Boreal once the young have hatched during summer. This includes everything from shorebirds and songbirds to raptors and waterfowl, with songbirds being the most numerous. In terms of population, 30% of all landbirds, 30% of all shorebirds, and 38% of all waterfowl found in the U.S. and Canada come from the Boreal.

The combination of its size, habitat diversity, and especially the prominence of lakes, rivers, and wetlands are what draw such large crowds. Songbirds that thrive in dense thickets find comfort in the thickly-treed southern portion of the forest, whereas shorebirds and waterfowl that opt for large, expansive open spaces are attracted to the wetlands and millions of shimmering lakes that speckle throughout the landscape further north.

In fact, as many as 325 bird species—nearly half of all those found in the U.S. and Canada—substantially rely on the forest for breeding grounds or migratory stopover habitat.

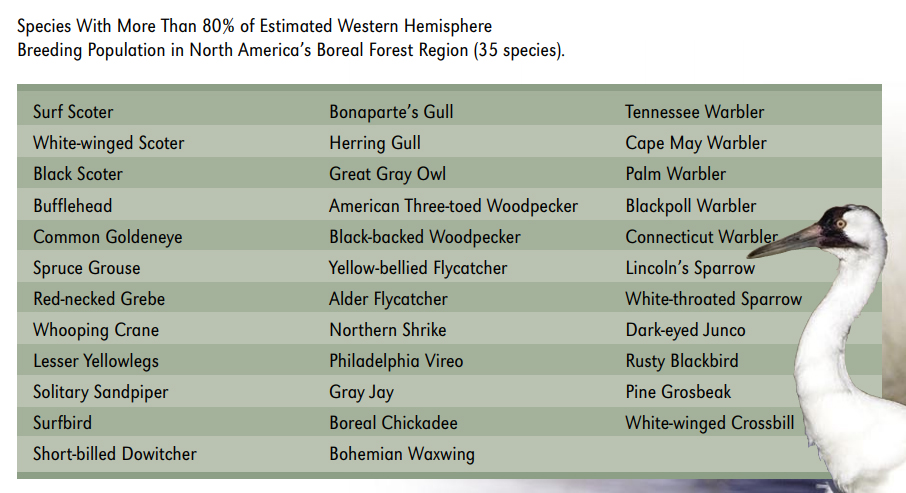

So if you’ve ever enjoyed watching a Bohemian Waxwing plucking berries from a nearby shrub, a Bufflehead or Black Scoter dabbling in a lake or along the shoreline, a Cape May, Tennessee, or Blackpoll Warbler flashing amongst the trees, or soaked in the sweet melody of a White-throated Sparrow, there’s a very high chance you owe that experience to the Boreal Forest.

For these and dozens of other species—35 to be exact—almost all of their North American populations are dependent on the Boreal:

If this is in fact the first time you’ve learned about the Boreal Forest, rest assured that you’re not alone. Even within the scientific community, the Boreal is just beginning to receive the recognition it deserves alongside tropical forests.

You can, however, play a part in making sure this continental-scale gem remains healthy for decades to come and continues to be able to produce the migrants we gawk at as they traverse through their epic migration cycles.

And the easiest way you can help is simple: chirp up about it.

With the number of born-in-the-boreal birds that those of us further south see during fall, winter, and spring, talking about it amongst your friends and colleagues shouldn’t be too difficult.

A much smaller proportion of the Amazon would be protected today had the international community not identified it as an important area and educated children about its size and amazing biodiversity.

It starts with learning which of the bird species commonly found in your region have origins in the Boreal Forest. To make it easier, we have boreal-specific species lists for most major U.S. cities. Simply find the city closest to you and pour over the list to see which species you’ve seen before or anticipate seeing in the future. Or take a look at the full list of common boreal birds to see which ones you recognize.

Of course, there are more hands-on ways to help.

We feature new stories and ways you can help boreal birds in our E-updates, which is the best way to stay up to speed on emerging conservation opportunities and to voice your support. You can sign up here (it will ask you to fill out multiple boxes after entering your email—first name is the only one that is mandatory): http://www.borealbirds.org/boreal-bird-e-updates

If you’d like to dig your claws into something a bit more direct and tangible, a particular region in need of better protection is the vast and still-pristine expanse of wetlands that form the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands. This region—the second largest wetland network on Earth—is enormously important for shorebirds and waterfowl, but also a surprising number of songbirds, such as the Palm Warbler.

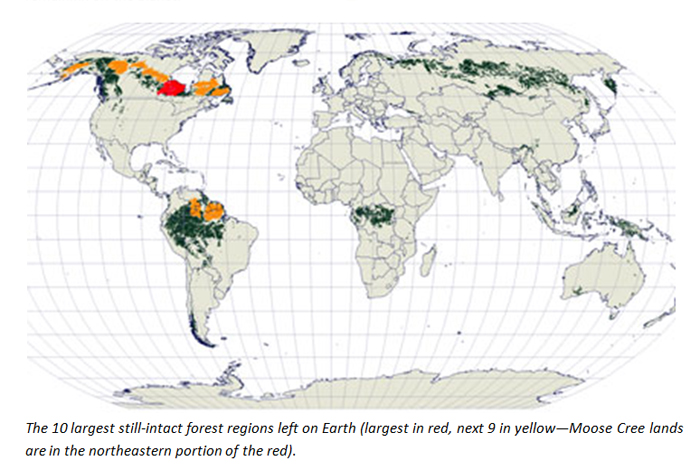

The Moose Cree First Nation is leading an effort to protect much of their traditional territories, whose lands and waters extend throughout the region near James Bay. This area accounts for a sizable portion of what is likely still the largest contiguous expanse of undisturbed forest (no roads, no power lines, etc.) remaining on the planet.

However, interest in the region among mining companies has increased recently and the Moose Cree would like to set aside some of the most culturally and ecologically important lands and waters before exploration and development can occur.

If you would like to help, consider sending an email in support. The Ontario-based Wildlands League have a pre-drafted email in place, but you’re more than welcome to tailor it however you see fit.

Our mission is to make the Boreal Forest the best-protected large forest region on Earth. We, and surely billions of birds, will be grateful for anything you can do to help us keep the Boreal Forest singing for generations to come.