The following is a guest post generously shared with us by Gerhard Bruins, Bird Surveys Biologist with the Canadian Wildlife Service.

Credit: Candice Talbot

After two weeks of shorebird watching on the saltwater shores of James Bay, the migration highway for shorebirds, I am back. I stayed at camp Longridge Point with some keen biologists and crack birders. It turned out to be a paradise for shorebirds and other wildlife.

The James Bay shorebirds project started in 2009 and is managed by Christian Friis of the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) with collaborators from the Royal Ontario Museum, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) and Forestry (OMNR), Bird Studies Canada, Trent University, Nature Canada and the Moose Cree First Nation.

Credit: Candice Talbot

Getting there takes some planning. Reaching the remote northern camp may take three or four days. From Ottawa I drove with some colleagues for eight hours to reach Cochrane. We stayed overnight at the North Adventure Inn. Other folks drove up from Toronto in two vans and a Cube Van loaded with literally hundreds of items including large plastic moving boxes filled with gear, personal backpacks, tools, mist nets and poles, Coleman stoves, propane tanks, generators and cryogenic shippers to store invertebrates and blood samples. Somewhere in there was also a two-week supply of food. The next day we took the five-hour train ride on the “Polar Bear Express” to Moosonee. The seats were spacious and comfortable and the train wasn't busy so lots of room to spread out. From the domed car we had a good view of the trees of the unspoiled boreal forest with the odd sight of water as the train traverses the Moose and Abitibi Rivers. We stayed overnight at the Waterfowl House of the OMNR. We got some help in moving our stuff from the local OPP. The next morning we had to shuttle to the airport with our stuff and were picked up by the OMNR helicopter for the ride to camp Longridge Point. No matter where your camp is located all your stuff needs to be flown in by helicopter.

The shores of James Bay are an important staging area for migrating shorebirds. Some long distance flyers like the Red Knot, have suffered dramatic declines over the years and have been classed as endangered. Surveying the tidal flat was a daily activity. Binocular-clad and lugging their scopes and tripods, surveyors splashed across kilometres of tidal flats and noted all species and how many of each.

We bivouacked at the goose-hunting camp rented from the Moose Cree Nation. The camp has a portable electric fence that was set up around the food and kitchen cabin. Other cabins provide some basic protection from the elements. However, this was the first time I had to resort to a mosquito net for sleeping. The first night I asked my roommate if I needed netting during the night and he replied that the first mosquito was not too bad but it was the next 500 that were the problem. Funny guy. And yes, I did use my mosquito netting. Mosquitoes and deer flies provided for a constant buzz while they droned around our heads looking for a good spot to drill down their proboscis.

Credit: Candice Talbot

The wrack, the glorious wrack. What is wrack? It’s the common name for the huge deposit of plant material high on the beach. It consists of several species of seaweed brought up by high tide. The wrack is part of the shore just above the mean high tide where kelp is deposited on the sand. It is prime breeding ground for flies and other insects and thus a preferred feeding area for shorebirds as it is full of maggots and thousands of invertebrates. It is also a favorite for passerines, skunks and foxes.

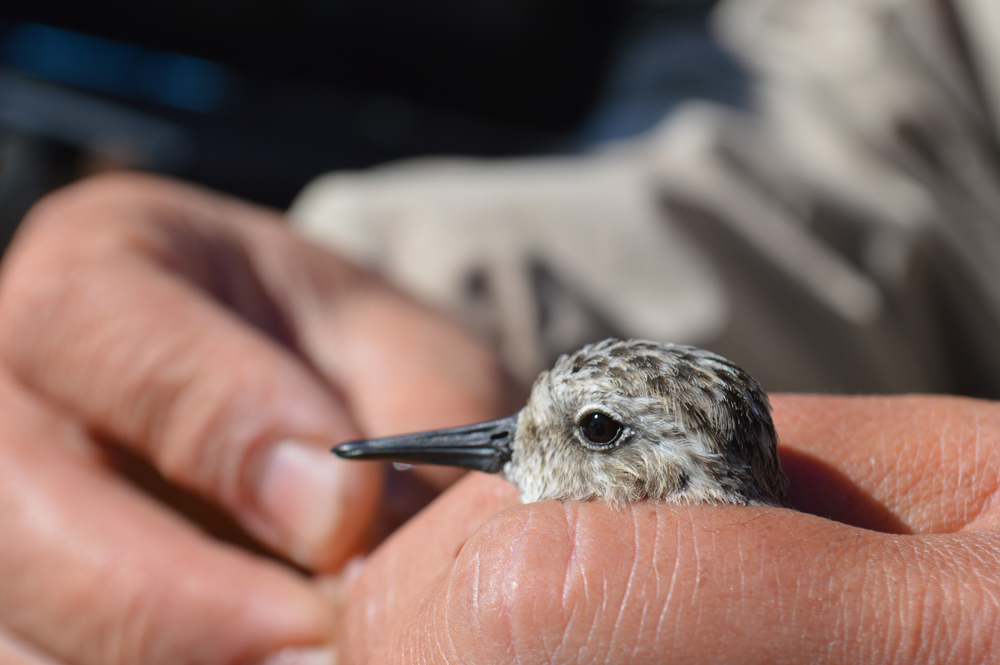

It was here on the wrack that we found hundreds of Semipalmated Sandpipers, Hudsonian Godwits, Red Knots and Ruddy Turnstones, just to mention a few. We quickly decided to install our whoosh net for capturing shorebirds.

Credit: Candice Talbot

On day one while strolling the beach all the way up to the sand spit which is the sandy point of Longridge Point we found a washed up Beluga.

On my second day at Longridge Point, out on the mud flats with a colleague surveying waders, a crackling sound woke up our walky-talky. The other team, who had just arrived at the gravel ridge near Bear Point (this is the actual name of this location), reported that they had come face-to-face with a large polar bear. They were within 30 meters of the frolicking animal who was running after some wading shorebirds. Now the panic set in and we were all ordered back to camp immediately. The probability of encountering a black bear along the James Bay coast is very high. However, being confronted with a polar bear was quite unexpected and had not happened before at this location. All a sudden we were to follow the “polar bear camp protocol”, which meant only going on an excursion in a large group armed with the Remington 12-gauge pump action shotgun loaded with bear slugs. Of course since we had only the one shotgun, no one was allowed to stay at the camp without protection. This new procedure limited our movement somewhat. We stayed in contact with the project leader and CWS headquarters and were reminded that bear spray and bear bangers (noise makers), good to deter black bear, are absolutely useless when it comes to shooing a polar bear. We went back to Bear Point the next day and I had a chance to measure the paw print on the beach, about 35 cm long.

Credit: Candice Talbot

In addition to counting the shorebirds present, emphasis was placed on observing flagged Red Knots, and determining the flag color and inscribed alpha-numeric code. These observations were compiled during a daily tally of all wildlife observations in and around our camp.

In the following days I found a cross fox, which is actually a melanistic variant of the red fox with black down its back and over its shoulder; also a grey wolf was observed on the mud flat. Its print measured 12.5 cm. It was acting like a big German shepherd. It looked like it was relaxing after a big meal, perhaps it had snacked on a Canada goose.

I had a wonderful time doing shorebird surveys along James Bay. For a bird nut like me it was a real tweet.

Credit: Candice Talbot

I identified the following species at Longridge Point:

Shorebirds: Black-bellied Plover, Semipalmated Plover, Killdeer, Spotted Sandpiper, Solitary Sandpiper, Baird's Sandpiper, Greater Yellowlegs, Lesser Yellowlegs, Whimbrel, Hudsonian Godwit, Ruddy Turnstone, Red Knot, Sanderling, Dunlin, Least Sandpiper, Semipalmated Sandpiper, White-rumped Sandpiper, Pectoral Sandpiper, Wilson's Snipe and Wilson's Phalarope.

Other species: American Black Duck, Mallard, Northern Pintail, Green-winged Teal, Common Goldeneye, Common Merganser, Red-breasted Merganser, Ring-necked Duck, Common Loon, American Wigeon, Greater Scaup, White-winged Scoter, Black Scoter, Canada Goose, Double-crested Cormorant, American White Pelican, Yellow Rail, Sora, Bonaparte's Gull, Franklin's Gull, Gray Jay, Blue Jay, American Crow, Common Raven, Red-winged Blackbird, Black-capped Chickadee, Boreal Chickadee, American Robin, Red-eyed Vireo, Cedar Waxwing, Swainson's Thrush, Sandhill Crane, Rusty Blackbird, Clay-colored Sparrow, Savannah Sparrow, Song Sparrow, Nelson's Sparrow, Le Conte's Sparrow, White-throated Sparrow, Chipping Sparrow, Swamp Sparrow, White-winged Crossbill, Osprey, Bald Eagle, Northern Goshawk, Northern Harrier, Short-eared Owl, Merlin, Peregrine Falcon, Great Black-backed Gull, Ring-billed Gull, Herring Gull, Arctic Tern, Common Tern, Alder Flycatcher, Lincoln's Sparrow, Yellow Warbler, Tennessee Warbler, Magnolia Warbler, Nashville Warbler, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Black-and-white Warbler, Northern Waterthrush, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Purple Finch, Hairy Woodpecker, European Starling and Common Nighthawk.

Credit: Candice Talbot