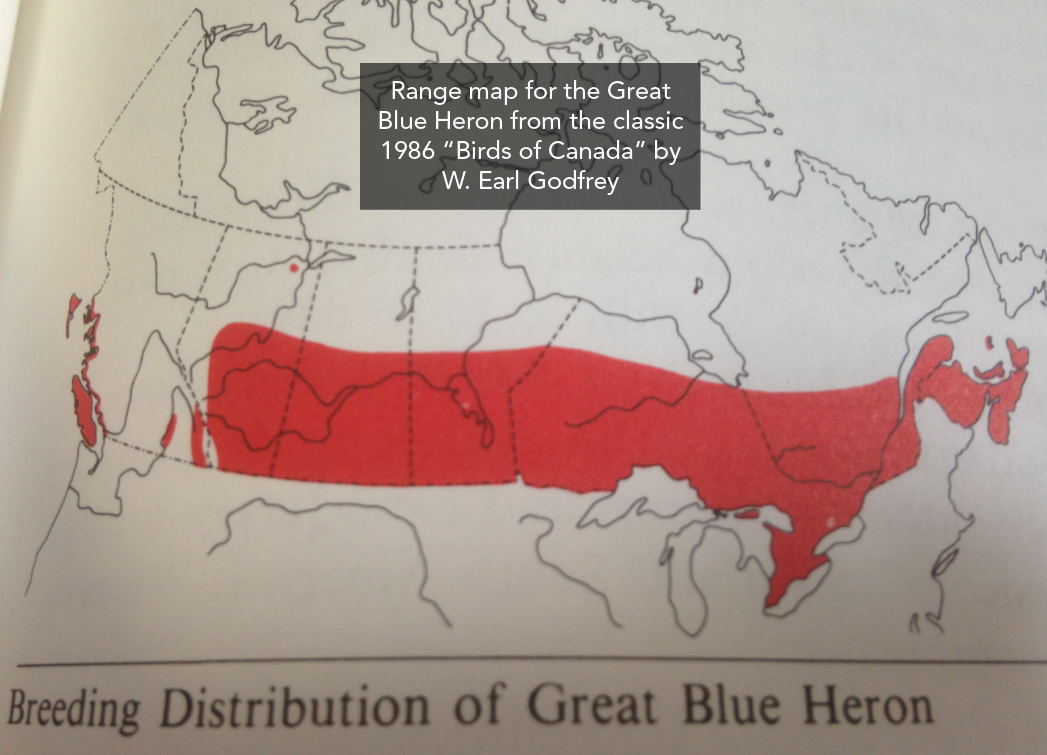

The Northwest Territories News/North newspaper recently reported that birders had spotted a Great Blue Heron in Hay River, a town along the southwest shore of Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories. In southern Canada and the U.S. such a sighting wouldn’t get much attention since Great Blue Herons nest throughout that region. But they don’t nest in the Northwest Territories (the only regularly seen bird that is remotely similar is the Sandhill Crane) so on the rare occasion when one shows up, it is big news.

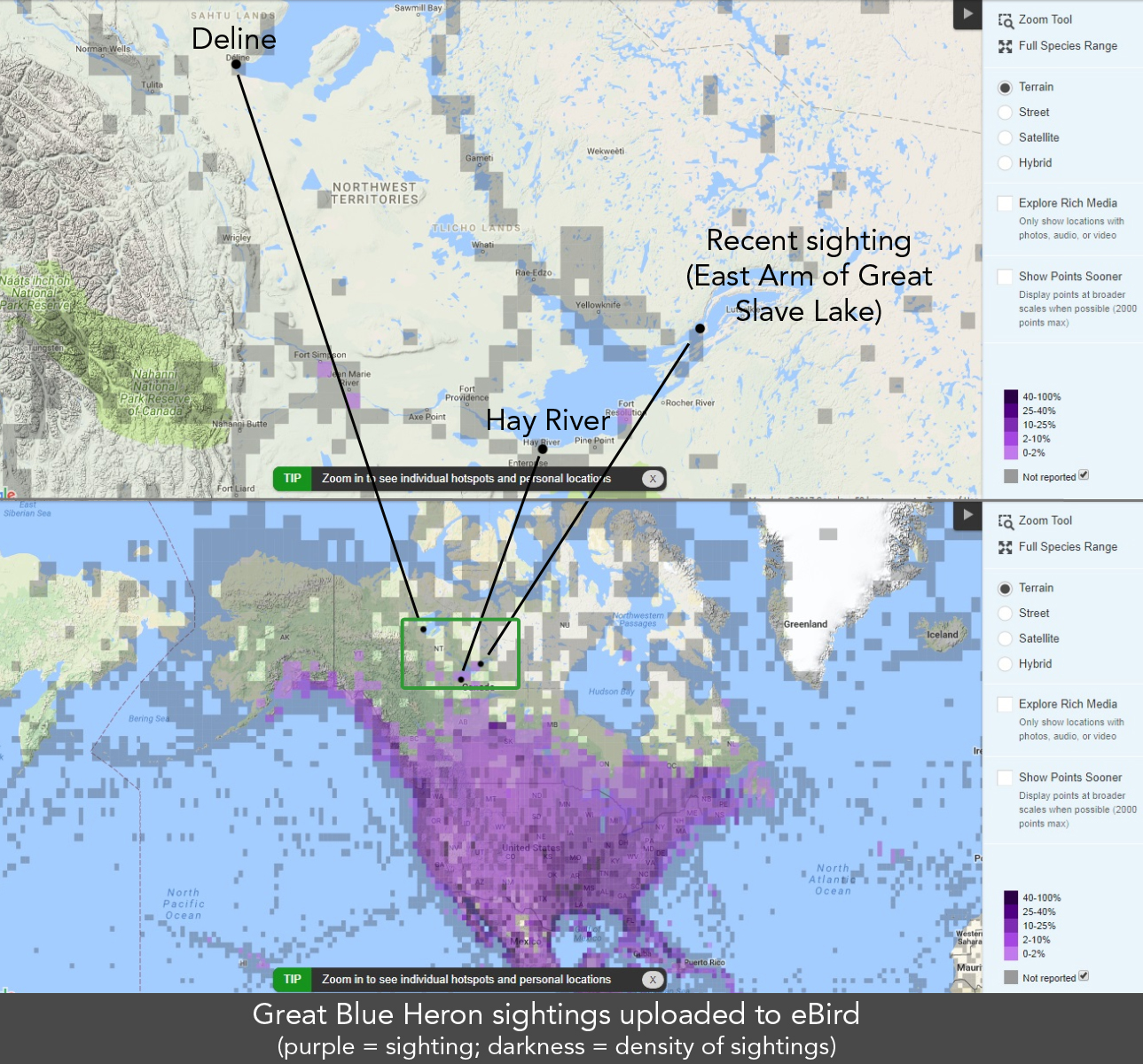

Herons and egrets are known for the tendency of young birds to wander in late summer and early fall after achieving independence from their parents so it is not completely out of character to find the odd individual that journeys further than others. But still, there are precious few records of Great Blue Herons as far north as the Northwest Territories. In fact, eBird (the online database of bird records from Cornell and Audubon) shows only four records of Great Blue Herons in the Northwest Territories prior to this summer and two of those are within the last five years.

Along with the Hay River recent Hay River sighting, eBird reports a sighting from the East Arm of Great Slave Lake in early August of this year. Last summer a Great Blue Heron that arrived in the tiny community of Deline on the shore of Great Bear Lake (the latter having been recently enshrined as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve thanks to the forward-thinking vision of the community itself) made an even bigger stir since it was many hundreds of miles further north than any others ever seen in the region.

Sightings of these and other previously more southerly species further and further north in the Northwest Territories fit a pattern that is becoming familiar with those tracking the changes of a warming climate.

Here are some photos from Michael Neyelle, who lives in Deline and is President of the aformentioned Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve. He was able to capture these shots from his front yard when the Great Blue Heron showed up in the area in 2016:

A recently released scientific study that tracked the migration timing of the famously rare Whooping Cranes that nest in Wood Buffalo National Park (straddling the Northwest Territories/Alberta border), also documented the impacts of the warming climate. These birds, whose population had dwindled to only 15 or 16 birds by 1940, have made an incredible comeback and now number in the hundreds. Researchers have closely tracked the times they leave their wintering grounds along the Texas coast and arrive in Wood Buffalo National Park and vice versa. The scientists found in looking at these years of migration timing data that the bird’s spring migration is 22 days earlier than it was 65 years ago and fall migration is 21 days later (see study here).

Luckily for the Whooping Cranes, later migration may lower their risk of being on the wintering grounds during hurricane season. Hurricane Harvey, in fact, made landfall at the center of their wintering grounds and might have been devastating to the population if the birds had been there. Scientists and conservationists are still waiting for an assessment of how their wintering habitat may have been affected by the hurricane.

Yes, birds are showing impacts from climate change everywhere. The Boreal Forest region of Canada and Alaska though is one of the potential bright spots in these challenging times. That’s because the Boreal Forests’ intact forests, wetlands, peatlands, rivers and lakes have some unique and critical characteristics to help deal with climate change.

First, the Boreal Forest region is one of the world’s largest cold storage depots for carbon, much of it thousands of years old, and trees and mosses and other plants continue to pull more carbon out of the atmosphere. Second, the intact nature of many portions of the Boreal Forest give current animals and plant occupants their best chances of maintaining healthy and wide-ranging populations that can be resilient to the changes being imposed by a changing climate. These large blocks of intact habitat, free of the kinds of human-made obstacles like roads and powerlines found further south, will also allow species that are forced to shift their distributions northward to do so more readily.

Taken together these characteristics point to the critical need to maintain large blocks of intact habitat throughout the Boreal Forest to give wildlife and plants the chance to survive in our changing world.