Lucien Turner spent 1882-1884 in the Ungava Peninsula.

Sometime last year I was in Washington D.C. for a meeting and I had a window of free time in the morning. I contacted my friend and colleague, Smithsonian anthropologist Stephen Loring and sat down for coffee with him for a few minutes. Stephen is an amazing person with a long history of working in northern Canada and especially in the Ungava Peninsula of northern Quebec and Labrador. He is also a gifted storyteller who can bring to life a faraway landscape even sitting in a cloistered coffee shop in downtown D.C.

Stephen presented me with a copy of a book (for which he had contributed an essay) whose title tells nothing of the deep history and knowledge and mystery contained within its pages. The book is titled “Mammals of Ungava & Labrador” and was published by the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press in 2014. Its subtitle provides a bit more context: “The 1882-1884 fieldnotes of Lucien M. Turner together with Inuit and Innu Knowledge.”

The story of Lucien Turner alone is compelling. Turner was sent by the Smithsonian Institution to northern Ungava where he lived from 1882-1884. While there, he collected thousands of specimens of animals, plants and photos as well as enthnographic material. Turner also wrote thousands of pages of observations, sometimes writing so much that he injured his hand and could not write for months. The writings included collecting many stories told by the Inuit and Innu people that he came to know. After Turner’s return to the U.S. he wrote at least six lengthy manuscripts but, sadly, only two of these were every published and his original field notes have never been found. Tragically, his long periods of time away from his family resulted in divorce and he also was not employed further by the Smithsonian and he died in apparent obscurity in San Francisco in 1909.

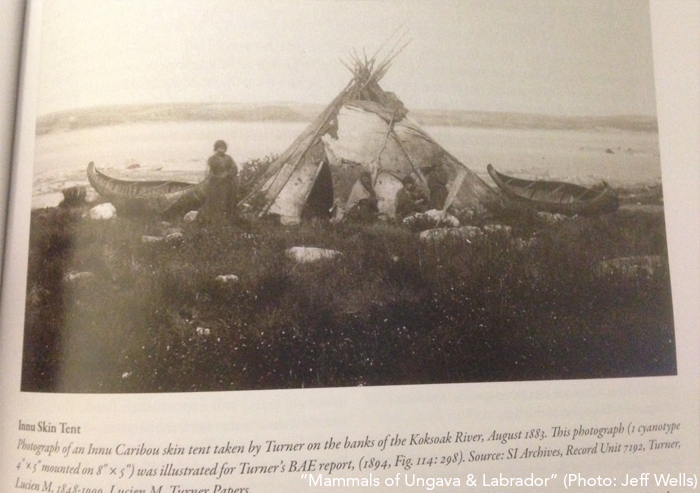

Editors Scott Heyes and Kristofer Helgen have done a masterful job of bringing Turner’s 130 year old work into a modern day context. They have taken his unpublished writings and provided them to us but with abundant contextual photos and other illustrations. There are many fascinating historical photos, some by Turner and others by photographers active around the same time period, giving a sense of what the places and people that Turner visited looked like at that time. Modern photos show a sampling of the thousands of specimens that he prepared and shipped back to the Smithsonian and that still can be found there.

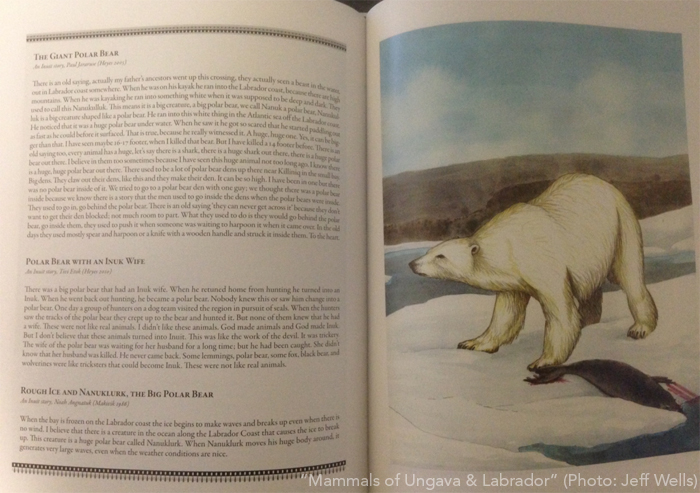

A large part of the book is made up the species accounts that Turner wrote about each of the mammal species for which he found evidence of occurrence in the region. The editors have richly supplemented Turner’s account with additional and modern information including the current scientific name and the modern regional Inuit language name, a current distribution map, and illustrations and photos. One of the most compelling parts of these accounts are the Innu and Inuit stories included here from both Turner’s manuscripts and from modern day Innu and Inuit elders.

One species account is about the intriguing and mysterious Barren Ground Bear, thought to have been a race of Grizzly Bear that inhabited the Ungava Peninsula, perhaps into the late 1800’s or early 1900’s. Turner wrote in his account that “The animal is not plentiful, although common enough and too common to suit some of the natives who have a wholesome dread of it.” He was not able to procure a specimen as any skin obtained by the Indigenous people of the area was considered too valuable to relinquish but he did obtain some bear lip ornaments that he thought were from this Barren Ground Bear. The editors include photos of these ornaments in the species account.

The Polar Bear account includes wonderful Inuit stores like “Polar Bear with an Inuk Wife” and “The Man Who Wanted to be Eaten” while the stories in the Wolverine account include those told to Turner by Innu elders like “A Wolverine Teaches Birds to Dance” and “A Wolverine Goes Begging Among Wolves.”

This book is a treasure trove of stories and knowledge about the Ungava Peninsula and its Inuit and Innu heritage and language that is an immense pleasure to read cover to cover or to thumb through to study the photos and stories. I recommend it to any readers who are enthralled with the North!