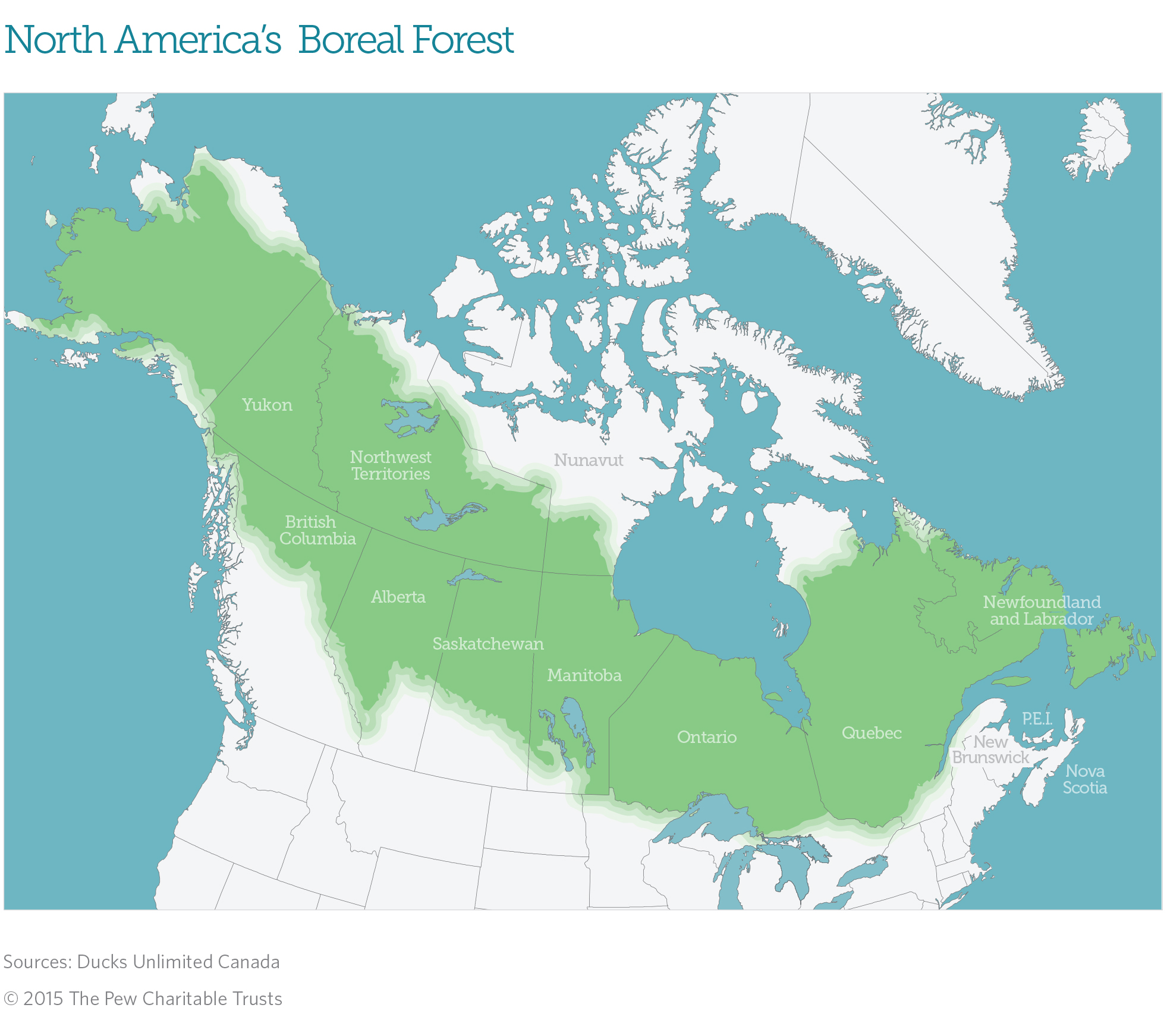

Canada has been blessed with one of the world’s most vibrant and expansive breeding grounds for migratory birds. The Boreal forest, which stretches across the northern third of our continent from Alaska to Newfoundland and Labrador, bestows 3-5 billion birds each summer that grace every corner of the Americas once the adults and their young have migrated south.

Migratory birds hatched in the Boreal forest winter from southern Canada and the United States, Central America, and the Caribbean all the way down to the southern tip of South America. A few species even have populations that fly to Europe, Africa, Asia, or Australia during their non-breeding period. Nearly half of the 700 species most commonly found in Canada and the U.S. rely on this international ‘bird nursery’ for breeding grounds.

More than 1 billion of these ‘Boreal birds’ return to the U.S. to bundle up for the winter. Connecting the dots between their breeding grounds and wintering habitat is critical to both advancing our understanding of birds in general and enhancing conservation and management efforts to preserve them over the long term.

A recent publication in The Condor, one of the world’s leading ornithology journals, provided some eye-opening insights into just how widely used some areas of the U.S. are for Canadian birds, and Boreal-breeding birds in particular. The authors also concluded that habitat management efforts in the U.S. should be broadened so that they don’t focus solely on the birds that breed in those areas but also include the winter birds that come largely from the Boreal forest region of Canada and Alaska.

The results of the study, which was conducted in two watersheds in California’s Central Valley, surprised the researchers. They discovered that riparian habitats that are typically managed to sustain breeding bird populations during the summer were just as heavily used during the winter, when measured in terms of number of bird species, and that the winter bird community was also more diverse overall.

Most of these winter bird species were birds that had a high proportion of their total breeding population in the Boreal forest region and included some that showed worrisome declines. Common Boreal-forest breeding species like American Wigeon, Bufflehead, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Varied Thrush, Lincoln’s Sparrow, and Golden-crowned Sparrow, were heavily represented in California winter bird communities.

Lincoln's Sparrow

Credit: Jeff Nadler

Studies and management techniques to preserve wintering species in riparian habitats in the U.S. are so overlooked that the researchers behind the study had trouble coming up with initial funding. Their patience paid off, however, as the results clearly show a need for better management of winter habitat for northern-born birds. They also believe that similar results will be found in other riparian habitats when conducted elsewhere in the U.S.

This has large implications given the vast number of birds (both in quantity and number of species) that are shared between Canada and the U.S.

While Canada and Alaska lay claim to possessing North America’s largest area of intact, primary forest and tundra habitats, the birds that nest there also need healthy habitats during migration and winter.

Fortunately, there are already many great efforts underway to conserve large portions of the Boreal forest region. The provinces of Ontario and Quebec have both pledged to preserve at least half of their northern Boreal regions, in line with the recommendations of modern conservation science, while many Indigenous governments and communities have made great gains to conserve their traditional territories throughout the Boreal, resulting in millions of hectares of bird habitat protected from loss and degradation.

This study underscores just how essential it is that Canada and the U.S. work side by side to preserve the birds we share.

As research, monitoring, and migratory tracking improve and data gaps are filled, it is imperative that we use this enhanced knowledge to develop conservation plans and implementation strategies that consider the full extent of their life-cycles from breeding grounds to wintering grounds and the migratory stop-overs in-between.

For the birds of the Boreal forest, there are no borders.